Finding the right game to satisfy the cravings that spring up during very specific moments of one’s life can be an exercise in frustration. Over the last couple of weeks I’ve been trying to find an MMO that gives me everything I want – rewarding progression, tiered equipment, quests that don’t bore me into the next millennia – while leaving out the tropes I don’t have time or patience to deal with. It’s from this discussion held with others, more exasperated bickering if I look back honestly, that some pervasive mechanics have come to light.

Why do people play obvious clones like Flappy Bird or Candy Crush Saga ? Since when did cute farming games become the gateway for grindfests? Seriously, when Farmville came out a couple years ago, I discovered parents that showed more dedication to their browsers than full-time dungeon raid groups did to their guilds. Worse yet, why do I still play League of Legends amidst a horrendous community and a UI that doesn’t show me what matters most?

The lengths that some people go to ensure their highscores remain high, or the effort individuals put into filling out all one-hundred-percent of those achievements, is what non-gamers (used in this context to mean anyone that literally does not play any video game, mobile shenanigans included) would classify as crazy. It certainly doesn’t feel crazy though.

There are properties of games that exist purely to keep gamers coming back. Most, if not all, of these mechanics are designed specifically to encourage that feeling of addiction. People using gamification to enhance (or, when applied to irrelevant fields that I shan’t get into here, diminish) the user experience tap into these factors. The psychology is material for scholarly papers, but for us it’s enough of a starting point to discuss the tricks designers utilize to have you pressing that subscription button for months to come.

The Social Aspect

This is the arch from which all other aspects dangle from. The tree that bears delicious fruit. The river that fills all downstream reservoirs. Games would not be nearly as popular if you couldn’t share your accomplishments and experience with others (note: this argument may still apply to single-player games as talking about campaigns and participating in fandoms counts as social interaction).

What makes communities valuable is the feeling you receive knowing that someone, somewhere out there, shares in your interest and sees the effort you’ve put in to accumulate social currency (from the idea of social capital). Essentially, the knowledge you’ve gained about a particular subject adds to your reputation within a community.

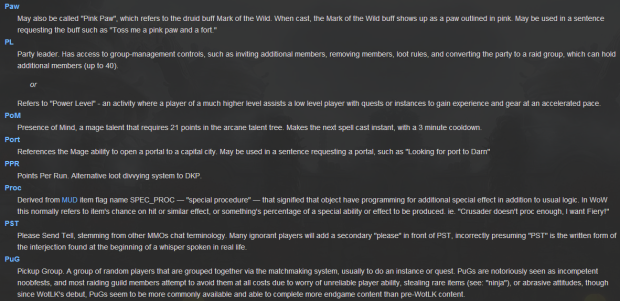

It’s easy to see this in action. Go into the chat room of any online game and start a conversation. If you’re familiar with all the terms, the nuances, the strategies, and the people, you’ll quickly find others who will, at the very least, hear you out. Compared to someone that has to ask what camping is, your words will have a lot more weight.

It’s intangible, but the recognition and awareness that you belong to a group is incredibly comforting. It’s the same itch you get when you see someone wearing a shirt with your favourite band or hear them offhandedly use a reference from a game you’ve played. That instant connection you feel is the marriage of a brand and a community.

And it’s even stronger when you’ve got rivals.

The quest to be the very best

Who doesn’t love a good competition? It’s a chance for you to test your skills against others of similar mind, to find out the result of your many hours of grinding. For some it’s an interesting bit of knowledge to see where you rank on the leaderboards, and for others it’s the reason why they play.

I never considered myself to be a hardcore math-junkie that crunches numbers for theorycrafting purely for the sake of crunching numbers. It wasn’t until I found EVE Online, the crowning achievement in spreadsheet simulations, that I realised I had an intrinsic addiction to numbers. More specifically, it was amusing to compare my numbers with everyone else’s.

In aiming to become better than our peers, we’ve turned to quantitative measures to simplify the analyses. Highscores, kill boards, hit counters, leader rankings. We’ve attached meaning to sequences of characters, and it’s these characters that we now show to others as badges of pride and honour.

Without having done anything directly, save for creating the system to allow competition to best propagate, developers can sit back while players engineer value within the game, for the game. A healthy competitive scene is the lifeblood of multiplayer games, because once the hard-coded quests are complete, people will need new goals to keep them occupied.

The daily grind

Of course, even in the presence of emergent play, there are some habits that find their way into the gaming landscape. No one likes obligations, least of all during our leisure time, but we’ve grown so accustomed to them that clicking away dailies becomes the work we do at home.

And really, dailies are an insidious way to ensure players remember a game. A task done every day for a month turns into a routine; the longer you keep at it, the harder it is to break away. Some cases it’s just another way to artificially lengthen the player experience. And then there’s Rift.

When dailies reward players after X number of completions with a bonus gift of gold or experience, they fall under the category of the benign. You can complete them if you want, but you’re not losing out on much if you don’t. However, as in the case with the aforementioned MMO, when the rewards are exclusive to the dailies they’re attached to, that’s when developers start to use guilt to lock your cell.

Need that last piece to finish your set? Better play tomorrow, and the day after that, all until the end of the week to collect enough doodads to trade in for a one-time-you’ll-never-see-it-again shiny thing. Missed a day due to sickness, work, or god forbid a life? Well then, I hope you’re willing to cough up millions to pay people who did grind endlessly in your place.

Do I sound bitter? Maybe a little. Excuse me while I go consume a chocolate bar.

The Pack Rat Syndrome

All right. Now that I have that out of my system (seriously, nothing has thwarted me so much from playing a game as the thought of some dev or publisher snickering as I login to do work after coming back from work), we move into the realm of collectibles.

Having stuff is nice, and the accumulation of virtual goodies is a very common goal. Being able to display what you’ve collected to the general public is even better, but as I’ve mentioned earlier, having people around to see what you’re up to usually adds to whatever you’re doing.

But there’s a special breed of collectibles that’s even more deadly than your ordinary baubles and trinkets. These are the randomly generated, items of chance that leave players chasing after percentages.

They come in two forms, both terribly deceptive, playing on the notion that hey, just because you didn’t get it this time around, doesn’t mean you should stop trying. In fact, the more you try, the more mystery boxes you open, the more bosses you kill, the greater your chance of obtaining the item you want!

Yeah. Independent probabilities don’t work like that, unfortunately. Rolling a dice a hundred times isn’t going to impact your next roll with the same dice. And yet, despite knowing this, I’ve fallen prey to the grindfest mentality that it’s only a matter of time before some valuable thing spawns in my inventory.

As an experiment, let’s say I was making naive calculations on the maximum time it would take to get the Golden Thief Bug Card, an extremely rare and sought after item for its magic-nullifying properties. We take the already ridiculous drop chance of 0.01%, figure out how many Bugs we would have to theoretically kill to make that 100%, and multiply it with how often we expect to encounter and kill the beast. I’m doing this by myself, including the actual locating of it, so say I take 10 minutes each time from spotting to killing. The thing spawns once every ~60-70 minutes. So, we have: 10,000 * (10 + 65) = 750,000 minutes. Which translates to 12,500 hours or just under 74.5 weeks.

As a side note, the poor logic we just did above actually does apply to a situation where we’re dealing with a closed pool of options. If you could guarantee that 1 out of every 10,000 Golden Thief Bugs would drop the Card, and that each Bug that spawns comes from the same pool of 10,000, then you are improving your chances with each kill.

The carrot at the end of the stick

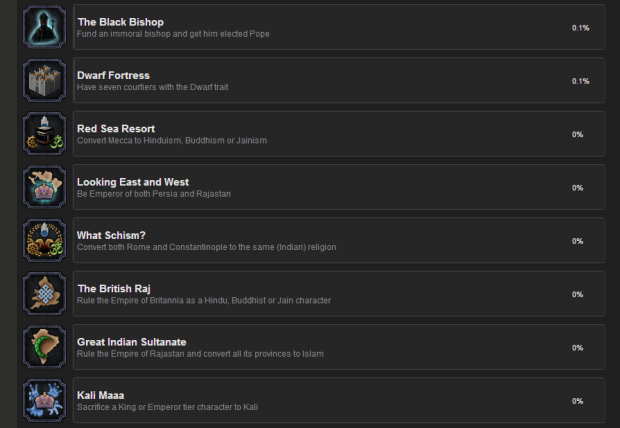

And lastly, the final nail in the coffin and the brother of the collectible, there are achievements. If the random-item-generator had you clicking away for a chance at some prize, the achievements are ways to reward your completion of (often times menial) tasks.

To sugar-coat what is otherwise absolute drivel – gather five-thousand acorns, win all modes with all characters even if that means playing the same thing sixty times, eat twenty pieces of poison fruit – it’s the numbers game all over again.

Achievements appeal to the desire for instant-gratification and the knowledge that you’re doing something right. Remember those stars you used to get in preschool for behaving during nap time or cleaning up after art lessons? They gave stars to kids because children don’t have the capacity (or want) to look way into the future to divine the long-term benefits of regular sleeping and hygiene.

Of course, there’s no tangible benefit to extract in collecting five-thousand acorns, but the idea holds.

As functional milestones, achievements pat you on the back for doing things that you otherwise wouldn’t because you either don’t care about or can’t be bothered with them. Like leaderboards, they’re easy ways to add more substance to a game without actually adding anything to the game.

From nothing we create value, giving points on a screen meaning when we aim to collect them.

So what of it?

These tricks of the trade contribute to the addictive quality of games. However negative my rant today has made them sound, and it’s hard to argue in favour of them since they’re designed with less-than-benevolent intentions in the majority of cases, they are fantastic ways of destroying time. It’s like what I tell people about gambling – the game is fun, and as long as you know what you’re getting into (and play responsibly, please), go for it and enjoy yourself.

Got a game that fits the bill, or found something equally frustrating that you just know was designed to make you play more? Leave a comment below!

Things mentioned in this article are very important. Though they are not the problem itself, game developers are often abusing them (and other tricks) and as a result they replace the whole gameplay with this stuff. These ‘mechanics’ could be a nice addition for the gameplay, but there must be some gameplay.

Many people mention ‘plot’ when they’re speaking about some games, and I don’t realy understand that, but when I’m reading game texts it is interesting for me or not. When I was playing “Planescape: Torment” I was enjoying almost every phrase in almost any description of something or dialog with NPC, dialogs in PsT made me think about different things… It was like a good book. And what about the ‘modern games’? When I’m trying to read texts in mosf of them it’s just making me want to sleep. There are some exceptions of course, like the upcoming “Age of Decadance”.

“Visual environment” – this is an important thing of the gameplay too. Look at the old adventures made by Lucas Arts (“Loom” for example) – you enter some location and first of all – you just stare at it, because it’s interesting, it looks nice, it is something unusual, it’s not the same as all other locations – there is some diversion, something unique. And this are low resolution images with very poor color palette, sometimes with animation made with color cycling. With the all new features, technologies and powerful hardware titans of the game industry can’t make nice visual environment, they only fill it with ugly models, blurred textures, oversaturated colors and glowing, shining, blurring effects of LSD trip… sometimes you can find a nice looking place or two, but that’s it.

…I guess I’ve got too far from the article already.

You could probably add things that “was designed to make you *pay* more” or just to make you “want to play” this game, but 5 ‘mechanics’ mentioned are… if not all then most popular things that you can see in almost any modern game.